Academic research is not about reading one paper at a time. When you work on a research question, you move continuously between different types of research papers, original studies, review articles, methodological discussions, and️ theoretical frameworks, often across years of published work. Each paper plays a specific role, and you need to understand those roles if you want to work efficiently and make defensible claims.

Knowing that different types of research papers exist is only the starting point. What actually matters is how you use them together, how you compare them, and how you position them within a broader body of literature. This guide explains the main types of research papers you will encounter and shows you how to work with them as part of a real research workflow.

Why understanding research paper types matters

When you search the academic literature, you are immediately faced with more papers than you can realistically read. If you do not understand what a paper is trying to accomplish, you will waste time on sources that do not support your research goal or give too much weight to papers that were never meant to serve as primary evidence.

You need to be able to tell, quickly and confidently, whether a paper introduces new data or synthesizes existing work, whether it is meant to answer a question or frame one, and how much authority it should have in your argument. When you understand research paper types, you stop collecting papers indiscriminately and start selecting them strategically.

This understanding also changes how you read. You should not read an empirical study the same way you read a review paper, and you should not approach a theoretical paper expecting results sections or datasets. Adjusting your reading strategy to the paper’s role makes your work faster, clearer, and far less frustrating.

The main types of research papers you’ll encounter

Across disciplines, journals use different labels, but most academic papers fall into a small number of functional categories. You should focus less on the label and more on what the paper contributes.

Original (empirical) research papers

When you read an original or empirical research paper, you are looking at where new evidence enters the literature. These papers present data collected or analyzed by the authors, and they form the foundation for most evidence-based claims. When you cite findings, this is the level you ultimately need to reach. You should read these papers closely, paying attention to methods, assumptions, and limitations, because weaknesses here carry forward into later work.

Review papers

Review papers serve a different purpose. You use them to orient yourself within a topic, understand how ideas have developed, and see where debates or disagreements exist. A strong review does not just summarize studies; it shows how research threads connect and where important gaps remain. You should treat review papers as maps, not as substitutes for original evidence.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses require even more care. These papers follow predefined methods to reduce bias, and meta-analyses combine results across studies to produce aggregate conclusions. In many fields, they are treated as high-level evidence, but you still need to understand what was included, what was excluded, and how differences between studies were handled before relying on their conclusions.

Methodological papers

Methodological papers focus on how research is done rather than what was found. You use them to understand tools, techniques, and analytical frameworks that shape an entire field. Even if you never cite them directly, they often influence how you design studies or evaluate the work of others.

Theoretical or conceptual papers

Theoretical or conceptual papers contribute by developing ideas rather than data. When you read these papers, you are not looking for results; you are looking for models, frameworks, and ways of thinking that shape how problems are defined and which questions are considered meaningful. Over time, these papers often exert wide influence by shaping how entire research areas evolve.

Why research paper classifications can be confusing

If you’ve ever looked up “types of research papers,” you’ve probably seen long and slightly contradictory lists. You’ll see many labels used to describe research papers, such as analytical, argumentative, or experimental. These labels often describe different aspects of a paper rather than clear academic categories.

In practice, research papers are usually described along three dimensions:

- Academic role, meaning what the paper contributes to knowledge

- Writing approach, meaning how ideas and arguments are presented

- Research method, meaning how data is generated

Because these dimensions overlap, lists of “types of research papers” can seem inconsistent or repetitive.

How researchers actually compare different papers

When researchers compare papers, they rarely do it in isolation. Instead, they look at how a paper connects to earlier work, how often it’s cited, and whether it relies on similar methods or theoretical assumptions as other studies in the field. Over time, patterns start to emerge, and individual papers make more sense as part of a broader conversation.

This kind of comparison is usually more informative than focusing on a paper’s formal category. It also encourages you to move beyond surface-level signals, like keywords, and toward understanding how research develops over time.

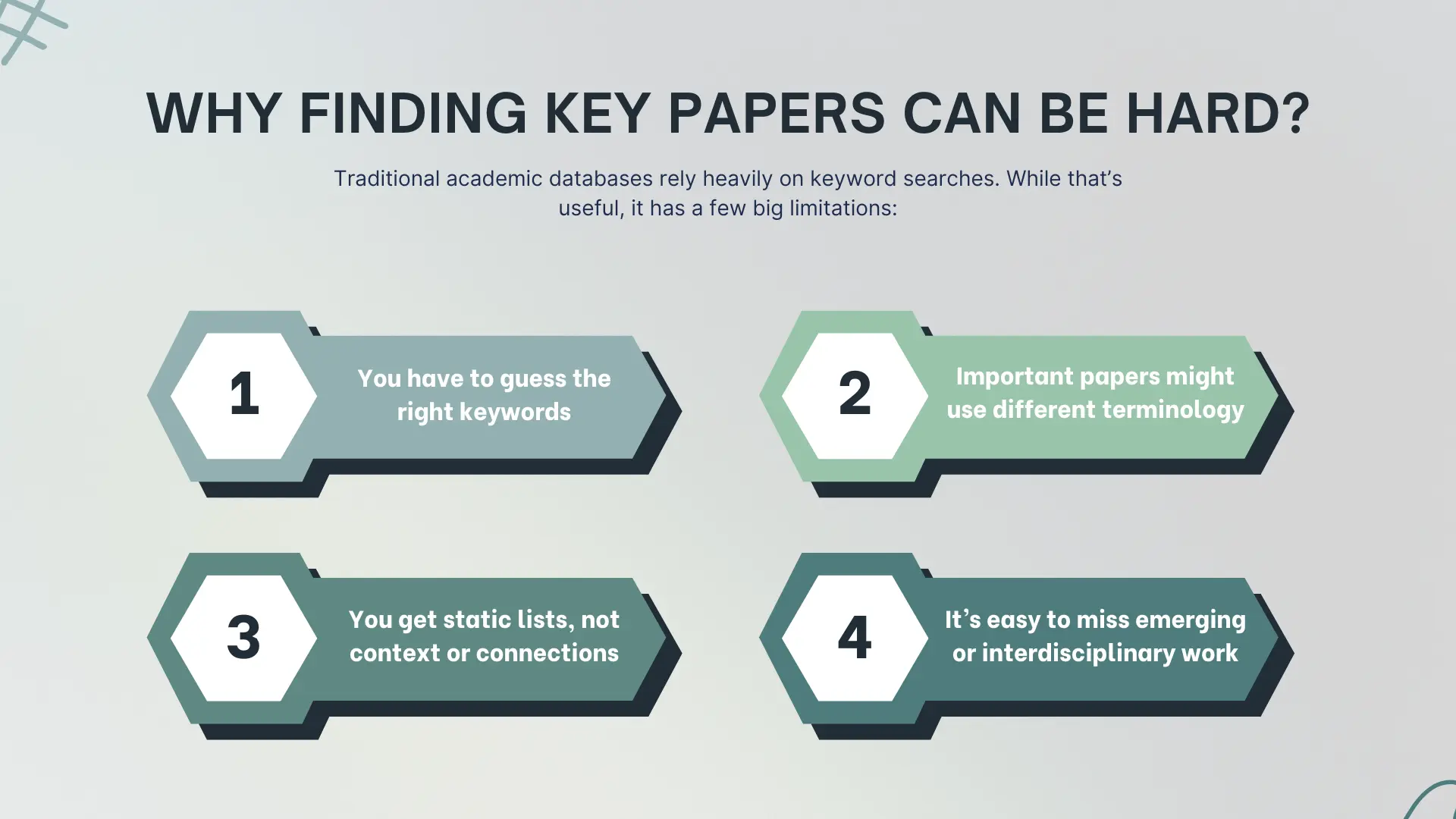

Why you need to move beyond keyword-based search

Keyword search is a useful starting point, but you cannot rely on it alone. It tends to surface papers that are recent, popular, or well optimized for search, while obscuring how studies relate to one another. As your research questions become more specific or complex, this limitation becomes a serious obstacle.

For this reason, you should explore literature through connections rather than keywords alone. Following citation links, examining shared reference lists, and tracing how ideas evolve across papers will reveal influential work that keyword matching often misses.

This is why forward-looking tools like ResearchRabbit are built on connection-first discovery. Instead of a static keyword list, they let you start with a single seminal paper and visually explore its citation network, instantly revealing foundational works and modern derivatives that keyword searches often miss.

How to approach research papers as connected bodies of work

When you stop treating papers as isolated results and start viewing them as part of an interconnected network, your understanding of a field changes. Foundational studies become easier to identify. Research trajectories become clearer. Differences between paper types make sense in context rather than in abstraction.

You should aim to work at this level whenever possible. Exploring relationships between papers allows you to compare evidence, theory, and methodology within a coherent structure, rather than jumping from one disconnected source to another.

This networked approach is exactly what visual literature-mapping tools like ResearchRabbit facilitate. They automatically generate maps of connected papers, allowing you to see these research trajectories and intellectual clusters form visually, making it intuitive to compare methodologies and identify influential theoretical frameworks.

Conclusion

Different types of research papers exist because they serve different purposes. If you want to work effectively, you need to recognize those purposes and use each paper accordingly. That means reading with intent, comparing papers relationally, and understanding how individual studies contribute to a larger body of knowledge.

This guide gives you a foundation for doing exactly that. By combining an understanding of research paper types with an exploration-first approach to literature, you can work more confidently, make stronger arguments, and navigate academic research with far greater efficiency. To put it into practice with a tool designed for connected exploration, start your first literature map in ResearchRabbit for free.

%20(800%20x%201036%20px).webp)

This is a big test comment on your article.