Introduction

If the title is the door to your research, the abstract is the welcome mat. It’s the very first thing readers, reviewers, and conference organisers see, and sometimes the only part they’ll ever read. A strong abstract makes your work stand out, while a weak one risks it being ignored.

The good news? Writing an effective abstract doesn’t have to be complicated. You just need to know how do you write an abstract for a research paper. just need to know How do you write an abstract for a research paper. With a clear structure and a few practical tips, you can create an abstract that captures attention and communicates the essence of your research.

What is an abstract? why write one?

An abstract is a short, self-contained summary of your research paper, typically 150–250 words. Think of it as your elevator pitch: in just a few sentences, you explain what you set out to do, how you approached the problem, what you discovered, and why it matters.

The abstract isn’t a replacement for your paper, it’s your marketing tool. It helps readers quickly decide whether the full text is worth their time. In databases and search engines, the abstract is often the only part people see, so you need to make it sharp, clear, and impactful.

You’ll need an abstract when you:

- Submit to journals (editors and reviewers will judge your work first by its abstract)

- Apply to conferences (organisers use it to select talks and posters)

- Complete theses and dissertations (abstracts are required for indexing)

- Write research proposals (funders often read the abstract before anything else)

In short: your abstract is your pitch, your marketing hook, and your first impression all rolled into one. Treat it seriously.

Types of Abstracts

Not all abstracts are created equal. The style you use depends on your purpose, audience, and requirements. Here are the four main types you’re likely to encounter:

- Critical Abstract

Don’t just describe, evaluate. A critical abstract goes beyond summary and comments on the strengths, weaknesses, or significance of the study. You might mention the validity of the findings, the reliability of the methods, or the contribution’s importance. These are rare in research articles but appear in reviews or annotated bibliographies.

- Descriptive Abstract

Keep it brief and factual. A descriptive abstract outlines your purpose, scope, and methods but skips results and conclusions. Think of it as a “table of contents in paragraph form.” You’ll often use this style in humanities or theoretical papers.

- Informative Abstract

This is the one you’ll use most. An informative abstract gives the complete picture: background, research question, methods, results, and conclusions. It gives readers enough detail to decide if your paper is relevant without reading the whole thing.

- Highlight Abstract

Here, your goal is to grab attention. You emphasise novelty, importance, or surprising insights. Highlight abstracts are common in conferences, posters, or promotional materials. Use them to spark curiosity, not to explain every detail.

What Should an Abstract Include?

A well-written abstract isn’t just a summary, it’s a mini version of your paper that highlights the most important elements in a clear, structured way. Most journals and conferences expect an abstract to cover four key components:

Problem / Purpose

- Clearly state what your research is about and why it matters.

- Answer: What gap in knowledge are you addressing? What question are you trying to solve?

- Example: “Despite the rapid growth of online education, little is known about how digital tools affect student engagement.”

Methods

- Briefly describe how you conducted the study: your approach, participants, data collection, or analysis techniques.

- Keep it concise—just enough for readers to understand the design.

- Example: “We surveyed 350 undergraduate students and conducted 12 interviews to explore engagement factors.”

Results

- Summarise the key findings of your research. This is often the part readers look for first.

- Be specific: use numbers or clear outcomes instead of vague phrases like “important results.”

- Example: “Students using collaborative tools reported 25% higher engagement compared to lecture-based platforms.”

Conclusions / Implications

- Highlight the meaning of your results and why they are significant.

- Link back to the bigger picture: how do your findings contribute to the field or solve the problem?

- Example: “These findings suggest that integrating interactive tools can improve learning outcomes in higher education.”

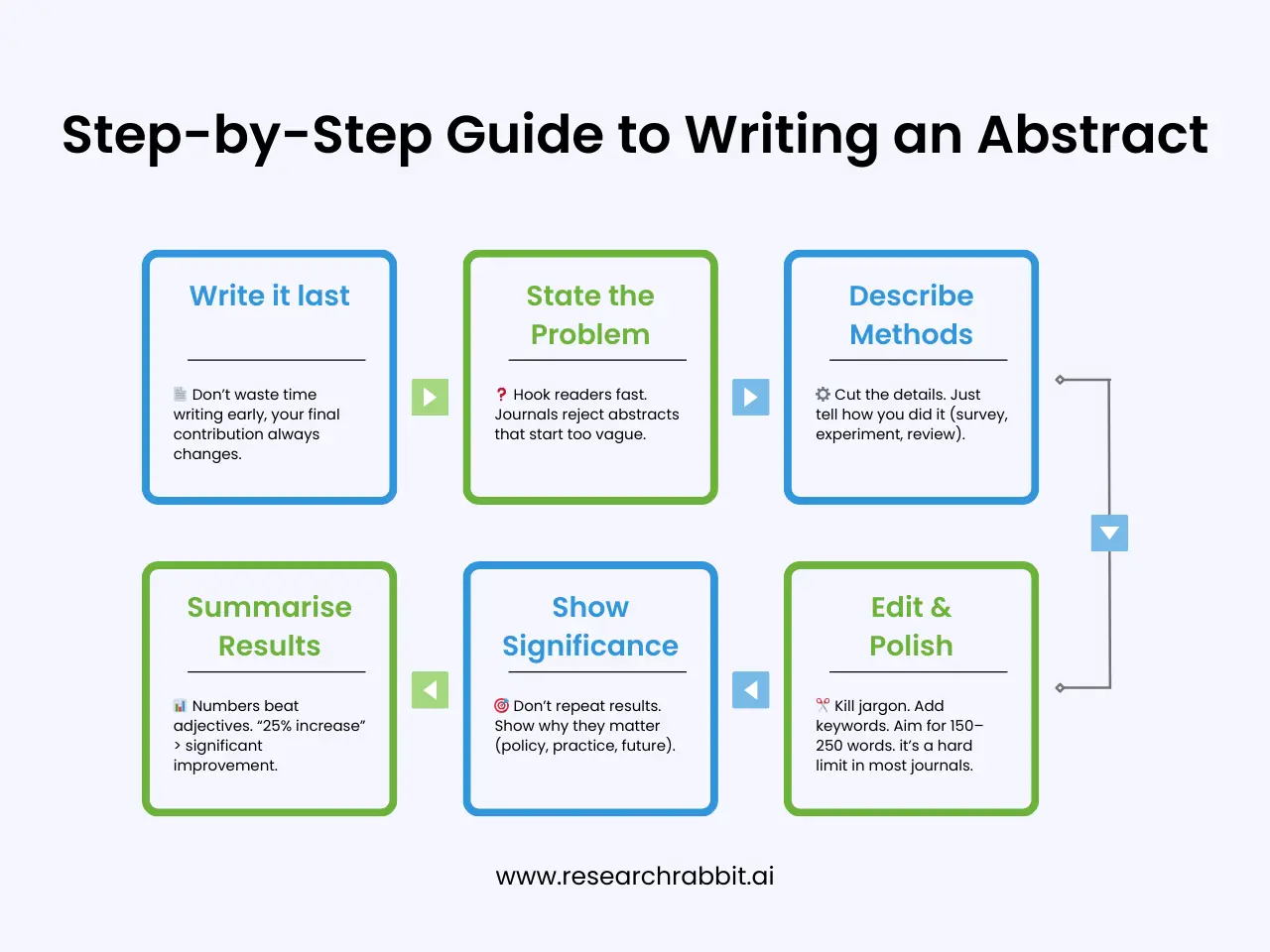

Step-by-Step Guide to Writing an Abstract

Writing an abstract becomes much easier if you treat it as a step-by-step process instead of trying to capture everything at once. Follow these steps to make process painless:

1. Write the Abstract Last

Don’t start with the abstract—it’s tempting, but risky. You’ll only know your paper’s true contribution after you’ve completed the introduction, methods, results, and discussion. Writing it last ensures accuracy and prevents contradictions.

2. Start with the Research Problem

Begin with one or two sentences that identify the central problem or purpose of your study. Be clear and specific.

- Example: “This study investigates the impact of digital tools on student engagement in online classes.”

3. Describe Your Methods

Briefly explain how you conducted your research—your design, participants, tools, or analysis. Focus only on essentials, not every detail.

- Example: “We surveyed 350 undergraduate students and conducted 12 in-depth interviews.”

4. Summarise the Key Findings

State the most important result or outcome. Be precise—if you have numbers, include them. Avoid vague phrases like “the results were significant.”

- Example: “Students using collaborative tools reported 25% higher engagement compared to those in lecture-only classes.”

5. Present the Conclusion and Significance

Explain what the results mean and why they matter. Link the findings back to the broader field or practical applications.

- Example: “The findings suggest that integrating interactive platforms can improve learning outcomes in higher education.”

6. Check Length, Clarity, and Keywords

Finally, edit for readability. Stay within the required word count (usually 150–250 words). Remove jargon. Make sure the abstract can stand alone without the rest of the paper. Add relevant keywords for indexing in academic databases.

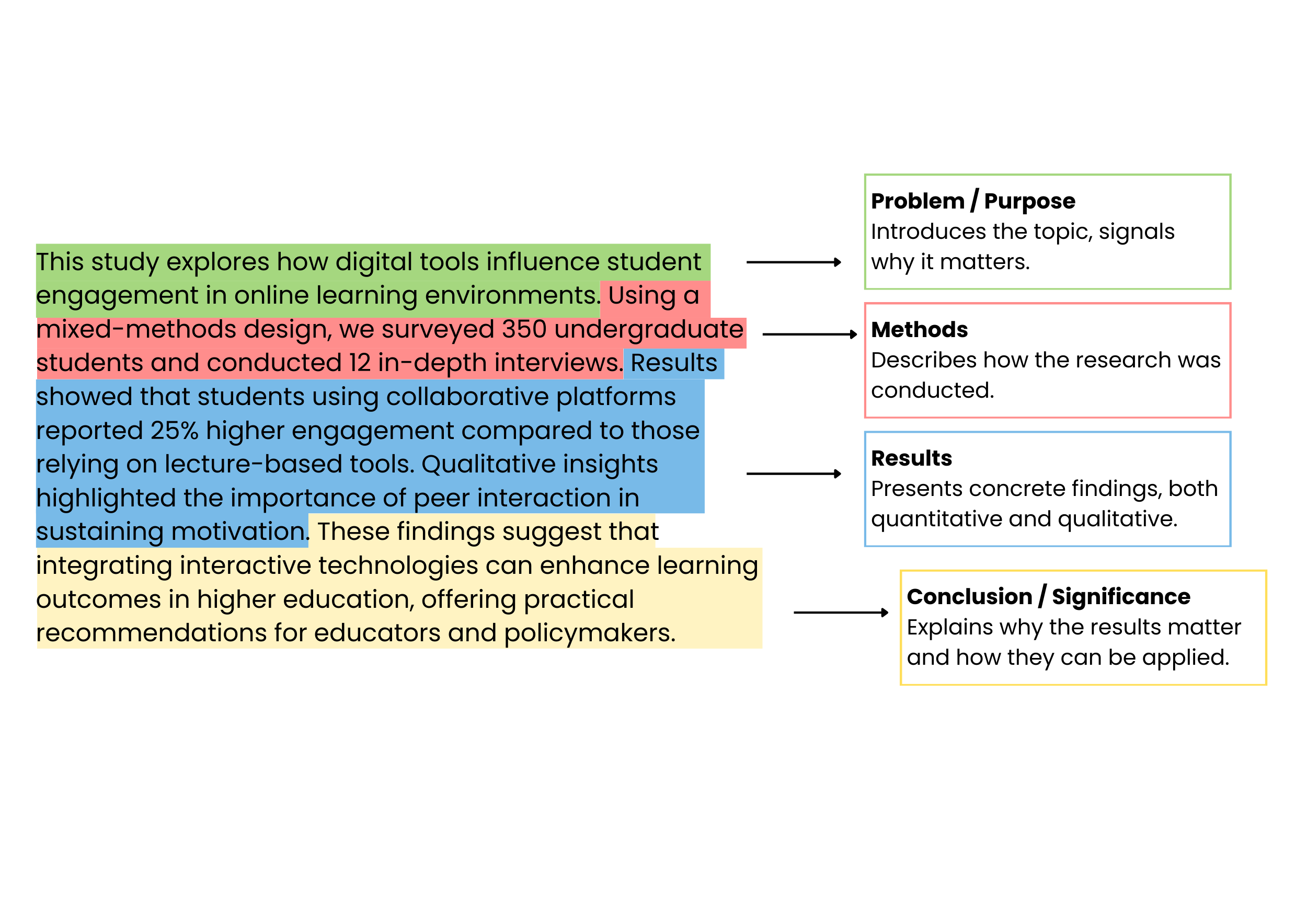

Example of an abstract for research paper

Below are three Sample abstract for research paper from different fields. Each shows how to structure a concise, informative summary that answers the key questions: problem, method, results, and conclusion

Example 1: Online Learning (Informative Abstract)

Title: The Impact of Digital Tools on Student Engagement in Online Learning

Abstract:

This study explores how digital tools influence student engagement in online learning environments. Using a mixed-methods design, we surveyed 350 undergraduate students and conducted 12 in-depth interviews. Results showed that students using collaborative platforms reported 25% higher engagement compared to those relying on lecture-based tools. Qualitative insights highlighted the importance of peer interaction in sustaining motivation. These findings suggest that integrating interactive technologies can enhance learning outcomes in higher education, offering practical recommendations for educators and policymakers.

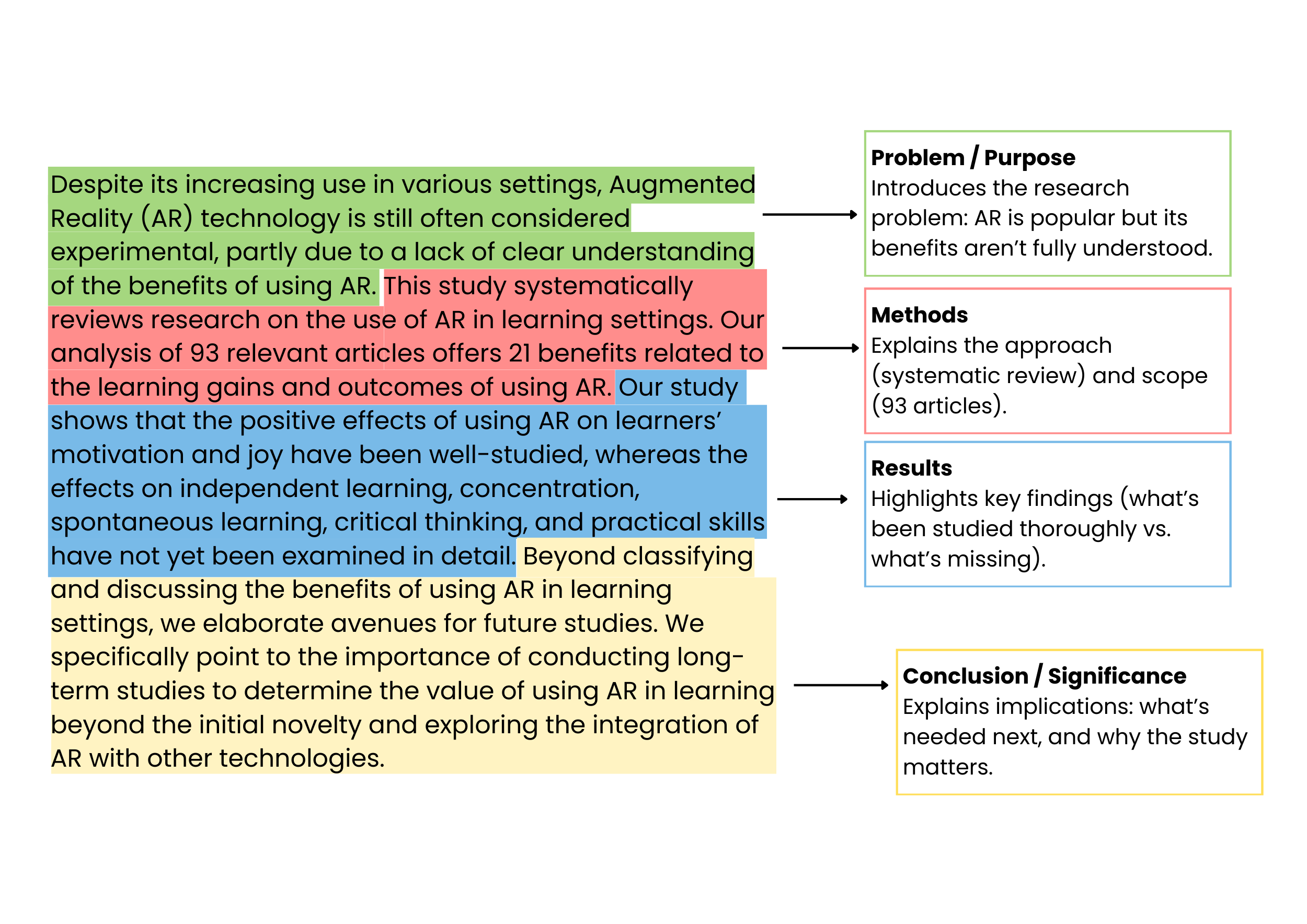

Example 2: Augmented Reality in Education (Systematic Review)

Title: Benefits of Augmented Reality in Learning Settings

Abstract:

Despite its increasing use in various settings, Augmented Reality (AR) technology is still often considered experimental, partly due to a lack of clear understanding of the benefits of using AR. This study systematically reviews research on the use of AR in learning settings. Our analysis of 93 relevant articles offers 21 benefits related to the learning gains and outcomes of using AR. Our study shows that the positive effects of using AR on learners’ motivation and joy have been well-studied, whereas the effects on independent learning, concentration, spontaneous learning, critical thinking, and practical skills have not yet been examined in detail. Beyond classifying and discussing the benefits of using AR in learning settings, we elaborate avenues for future studies. We specifically point to the importance of conducting long-term studies to determine the value of using AR in learning beyond the initial novelty and exploring the integration of AR with other technologies.

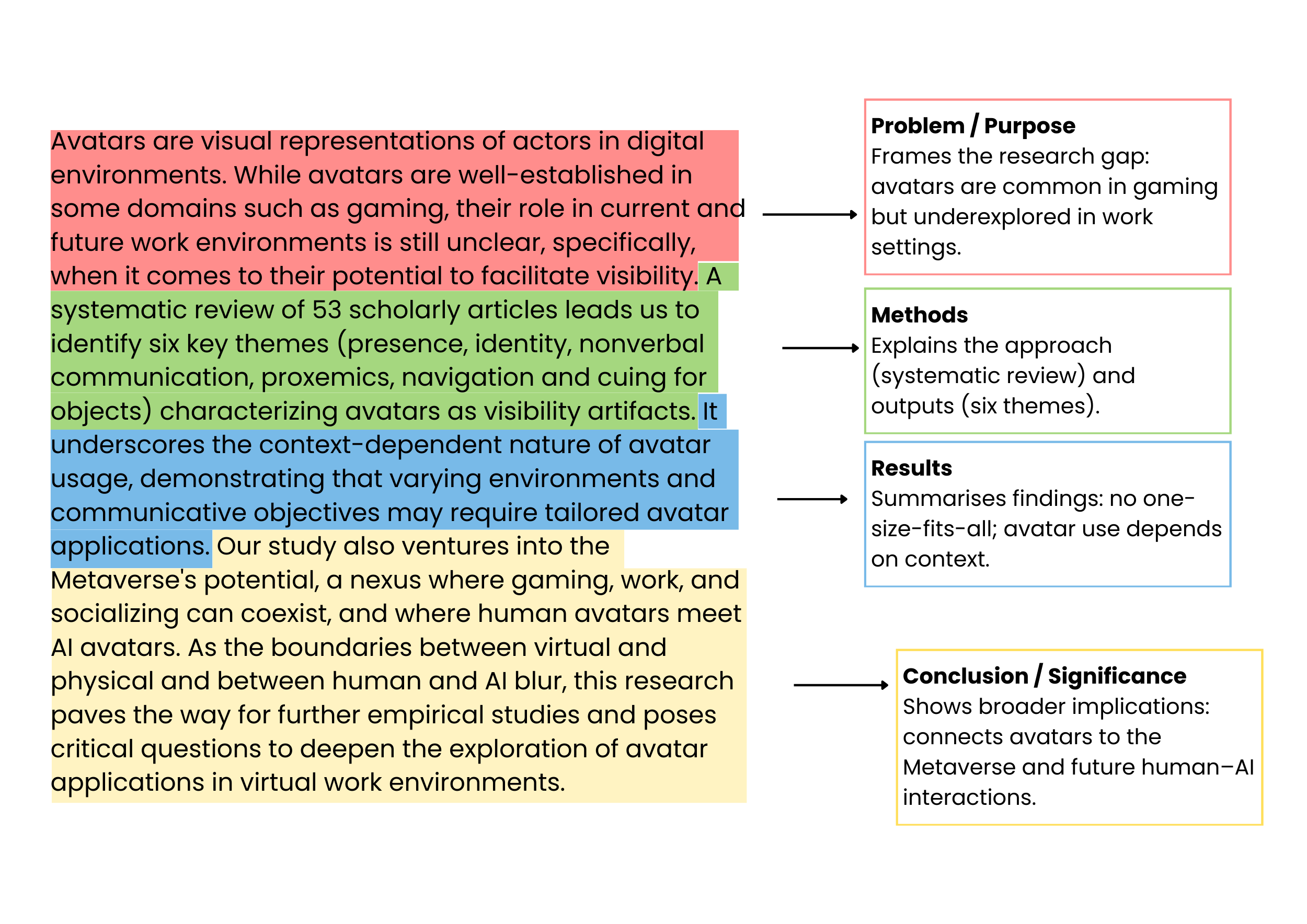

Example 3: Avatars in Digital Work (Systematic Review + Future Outlook)

Title: Avatars as Visibility Artifacts in Work Environments

Abstract:

Avatars are visual representations of actors in digital environments. While avatars are well-established in some domains such as gaming, their role in current and future work environments is still unclear, specifically, when it comes to their potential to facilitate visibility. A systematic review of 53 scholarly articles leads us to identify six key themes (presence, identity, nonverbal communication, proxemics, navigation and cuing for objects) characterizing avatars as visibility artifacts. It underscores the context-dependent nature of avatar usage, demonstrating that varying environments and communicative objectives may require tailored avatar applications. Our study also ventures into the Metaverse's potential, a nexus where gaming, work, and socializing can coexist, and where human avatars meet AI avatars. As the boundaries between virtual and physical and between human and AI blur, this research paves the way for further empirical studies and poses critical questions to deepen the exploration of avatar applications in virtual work environments.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing an Abstract

Don’t let these errors ruin your abstract:

- Writing before finishing the paper

You’ll end up with contradictions or missing details.

✅ Fix: Write it last.

- Adding references, citations, or figures

Abstracts must stand alone. Nobody wants footnotes here.

✅ Fix: Keep it clean and self-contained.

- Using vague phrases like “important results”

This tells readers nothing.

✅ Fix: Be precise—use numbers or concrete findings.

- Making it too long or too short

Over 300 words? Too much detail. Under 100? Not enough information.

✅ Fix: Aim for 150–250 words unless guidelines say otherwise.

- Copying sentences from the paper

This creates a patchwork instead of a clear summary.

✅ Fix: Rewrite and condense in your own words.

- Overloading with jargon

Remember: not everyone in your audience is a specialist.

✅ Fix: Use plain, accessible language.

Conclusion

Your abstract isn’t just a summary, it’s your paper’s first impression and its main selling point. If you want your research to get noticed, you need to write an abstract that’s clear, concise, and compelling.

So here’s your formula: state the problem, explain the methods, highlight the results, and show why it matters. Do it in 150–250 words, avoid fluff, and make every sentence count.

Tip: Use tools like ResearchRabbit to explore abstracts in your field and see how successful papers structure theirs. Studying good examples will sharpen your own writing.

_cover.webp)

%20(800%20x%201036%20px).webp)

This is a big test comment on your article.